Relive the moment that Julia Child became an American icon

At age 50, an unknown cookbook author from Cambridge debuted “The French Chef,” coined a catch phrase, and created a legend.

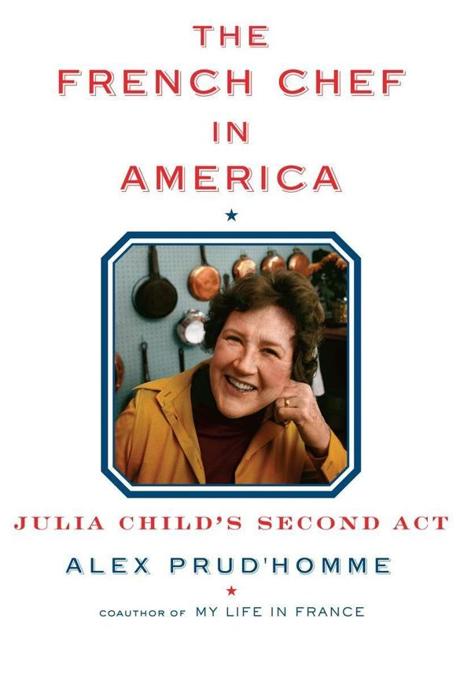

A 1974 photo of Julia Child, taken by her husband, Paul, eight years after “The French Chef” won educational TV’s first Emmy.

The author, Paul Prud’homme, will read from “The French Chef in America” at Wellesley Books on Oct. 17.

ON MAY 19, 1961, PAUL CHILD QUIT HIS JOB after 16 years in the Foreign Service. “Ah, freedom at last — no more of this hurly-burly, thank you very much,” he and his wife, Julia, said to each other. Upon returning to the States from Norway, the Childs moved into 103 Irving Street in Cambridge and set to making it their own. There were many refinements to be made, especially to the kitchen.

Julia didn’t care about establishing the “golden triangle” — a configuration allowing a cook to take as few steps as possible among stove, refrigerator, and sink — declaring in typical fashion “the more exercise the better.” But she was adamant that she have as much “working and putting-down space as possible.” The couple’s architect installed maple work surfaces, 1½ inches thick, along every available wall. The oven and the gas range, a six-burner Garland restaurant model that the Childs had purchased in the late 1940s for $400, required countertops nearby, as places for hot pans to rest and where oven mitts and basting brushes were at the ready. The counters were raised to 39 inches from the floor, to accommodate Julia’s 6-foot-2-plus height.

Shortly after moving to Cambridge, Julia met Dorothy Zinberg, a public policy expert at Harvard, at the Legal Sea Foods fish market. Looking over the haddock, lobsters, and clams, chatting with the store’s owner, George Berkowitz, the two women conversed as any other housewives might. Except that Julia Child happened to be unusually inquisitive and well informed about food.

The postwar culinary revolution was just getting underway in New York, but Cambridge was essentially a provincial New England town, Zinberg recalled, “like living in the country.” While Boston had some fine establishments, Cambridge restaurants tended to serve meat-and-potatoes basics or red-sauce Italian. “This was an era when dinner party menus consisted of grilled Spam, pineapple chunks, and gelatin-mold salad stuffed with marshmallows,” Zinberg said.

The Childs had a remarkable set of neighbors, most of whom lived within a few blocks of one another. The economist and former ambassador to India, John Kenneth Galbraith, and his wife, Catherine (“Kitty”), lived behind Paul and Julia. Book editor and friend Avis DeVoto lived close by, as did Dorothy and her husband, Norman Zinberg, who was an influential psychoanalyst at Harvard. Not far away were noted historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. and author and historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and his wife, artist and author Marian Schlesinger.

In Cambridge, there was a vast corps of overeducated, underemployed women who “were ready for Julia,” said Zinberg. “We didn’t know who she was at first. But then she changed our lives — in every way you can imagine.”

In October 1961, Julia published Mastering the Art of French Cooking. It was intended, she wrote, for “the servantless American cook who can be unconcerned on occasion with budgets, waistlines, time schedules, children’s meals, the parent- chauffeur- den-mother syndrome, or anything else which might interfere with the enjoyment of producing something wonderful to eat.” With a rave review in The New York Times, Craig Claiborne launched Mastering into the American mainstream, calling it “probably the most comprehensive, laudable, and monumental work” on French cooking in English.

Mastering arrived at an auspicious moment. The economy was booming, Americans were traveling abroad and eager to embrace new foods, and John and Jacqueline Kennedy had hired Rene Verdon to cook for them. Years later, Julia recalled: “With the Kennedys in the White House, people were very interested in [French food], so I had the field to myself, which was just damn lucky.”

On February 20, 1962, as Paul was transfixed by radio accounts of John Glenn’s orbit of Earth, Julia appeared on “an egghead TV show” called I’ve Been Reading. It was hosted by Boston College English professor Albert Duhamel and aired on WGBH, Boston’s fledgling public television station. Duhamel put Julia at ease, and she proved naturally comfortable in front of a TV camera. Perhaps too comfortable. So intent was she on demonstrating how to “turn” a mushroom and flip an omelet the French way that she forgot to mention the title of her book. But it hardly mattered. Twenty-seven people wrote to the station to say Get that tall, loud woman back on television. We want to see more cooking!

This was an unexpectedly warm response. The WGBH honchos looked at one another and wondered: Is there enough interest in this Julia Child to warrant a cooking show on public television?

THOUGH SHE DID NOT OWN A TV set, Julia had been bitten by the television bug from the moment she set foot on a studio set. She and her coauthor and best friend, Simone “Simca” Beck, had appeared on NBC’s Today show to promote Mastering, and afterward Julia wrote: “TV was certainly an impressive new medium.” (She would soon buy her first television with the proceeds from book sales.) By then, she had been teaching cooking for nine years and was on a mission to spread the gospel of “le gout francais” — the very essence of French taste — which she fervently believed could be reproduced by American cooks in their home kitchens. All that was needed, Julia said, were a set of clear instructions, the right tools and ingredients, and a little encouragement.

In April 1962, shortly after appearing on I’ve Been Reading, Julia typed a memo to WGBH in which she laid out a vision for “an interesting, adult series of half-hour TV programs on French cooking addressed to an intelligent, reasonably sophisticated audience which likes good food and cooking.”

Each program, Julia suggested, should focus on just a few recipes, and her cooking demonstration — “informal, easy, conversational, yet timed to the minute” — should lead to a discussion of broader culinary matters, such as “a significant book on cooking or wine, an interesting piece of equipment, or a special product.” Julia suggested that other experts, such as a pastry chef or a sommelier, appear as guests, and that well-known chefs — such as James Beard or Joseph Donon (a master French cuisinier) — cook side by side with her on the show.

WGBH had never produced a cooking program, had a small audience, was largely run by volunteers, and operated on a shoestring budget. But encouraged by the public’s strong response to Julia on I’ve Been Reading, the station arranged for her to shoot three trial episodes of a televised cookery show.

On June 18, 1962, the Childs arrived at a borrowed “studio” in downtown Boston — actually, the demonstration kitchen of the Boston Gas Co. — to shoot the initial pilot episode, “The French Omelette.” (Julia preferred the French spelling of that word.) Julia brought her own frying pan, spatula, butter, and eggs. The lights flicked on, and the show’s producer, 28-year-old Russell “Russ” Morash, directed two stationary cameras. Because videotape was so dear, the show was essentially shot “live” in one continuous half-hour take. “I careened around the stove for the allotted twenty-eight minutes, flashing whisks and bowls and pans, and panting a bit under the hot lights,” she recalled. “The omelette came out just fine. And with that, WGBH-TV had lurched into educational television’s first cooking program.”

The second and third pilot episodes, “Coq au Vin” and “Souffles,” were both shot on June 25. This time, Julia had rehearsed the shows at home. Paul built a replica of the set in their kitchen, labeled utensils, made sure the ingredients were measured beforehand, and coached Julia with a stopwatch. Though she continued to gasp and misplace things, she grew more self-assured with each performance.

Julia’s special sauce — her ability to blend deep knowledge, broad experience, precise technique, self-deprecating humor, and infectious enthusiasm — won the public’s heart. There was simply no one quite like her on TV. Julia loved this “high-wire act,” but admitted that she was “a complete amateur” and had no idea how she came across on TV. The answer was simple: The camera, and the audience, loved her.

In response to the “Coq au Vin” show, a viewer named Irene McHogue wrote: “Not only did I get a wonderfully refreshing new approach to the preparation and cooking of said poultry, but really and truly one of the most surprisingly entertaining half hours I have ever spent before the TV in many a moon. I love the way she projected over the camera directly to me the watcher. Loved watching her catch the frying pan as it almost went off the counter; loved her looking for the cover of the casserole.”

Encouraged, WGBH signed Julia up for a 26-episode series. Ruth Lockwood, the assistant producer, scrounged up a track of bouncy French theme music. Unable to decide on a name for the program, Julia called it The French Chef — though she was neither French nor a professional chef (she called herself “a cook”) — until she could invent a better title.

In the first episode, a slightly nervous, fresh-faced Julia demonstrated how to make boeuf bourguignon, the venerable beef stew that would run as a leitmotif through her career. At the end of the show, she tucked a dish towel into her apron, and spontaneously said: “This is Julia Child.Bon appetit!”

Child and members of WGBH’s production staff goof around on set.