Writing Pulia

“THOSE YEARS IN FRANCE were the best time of my life. It was the time when I discovered who I was and what I was about. It was so exciting that I hardly stopped to catch my breath!”

So Julia recalled in December 2003, when she was ninety-one and living in a retirement community in Montecito, California. I was Paul Child’s grandnephew. a young writer who had long wanted to collaborate with her on a book. But Julia was self-protective and for years had politely resisted the idea-until now, when she suddenly said something like, “Maybe we should try working on the France book together.”

We began the very next day.

For a few days every month, Julia and I would sit at a round table in the living room of her small, neat apartment in Montecito. I would read from the family letters that Paul and Julia had written between 1948 and 1954 when they lived in Paris and Marseilles, or from one of her cookbooks. I would ask her questions, and our conversations would evolve from there. Her health and memory were sometimes good, sometimes bad, and although should could only concentrate for an hour or so, working on the book energized her. At first I taped out interviews, but when I noticed Julia staring balefully at my tape recorder and poking at it with her long fingers, I realized it was distracting her. So I tried hiding the recorder behind the vase of roses she always kept on the table, but she quickly caught on and began fussing with the flowers. Julia claimed that the tape recorder didn’t bother her, but I could see otherwise and eventually gave it up and just took notes. After I had typed out a few vignettes, she would read them avidly, delete unnecessary words, correct my French and make amplifications in small, scratchy, right slanted handwriting in the margins.

Julia had an excellent recollection of food and people but was not so good on places. She gave me a lively description of her very first meal in France, in Rouen in November 1948, which she described as “an opening up of the soul and spirit for me”: a lunch of oysters portugaises, sole meuniere (“perfectly browned in a sputtering butter sauce with a sprinkling of chopped parsley”), and her first baguette. But when I asked what her apartment building in Paris had looked like, she stared at me with her big blue eyes, and with a little smile said: “Well, it was…a building.”

The French embraced the open-hearted, six-foot-two-inch Julia, who had a knack for charming grumpy policemen, mean waiters, and her “sour-ball” husband, a habit Paul described as “la Julification des gens.”

Sometimes when I mentioned the names of famous chefs she had known in Paris – Mangelotte, Thillemont, Calvert – Julia seemed to go into a kind of trance, and she would start reliving her first day of classes at La Cordon Bleu, or the night Colette held court at Le Grande Vefour, or the day she learned to bake proper baguette, o the fantastic eightieth birthday party she’d attended for the gastronome Curnonsky, who later “fell off his balcony to his death, and we never knew if it was an accident or suicide.”

Julia and Minou.

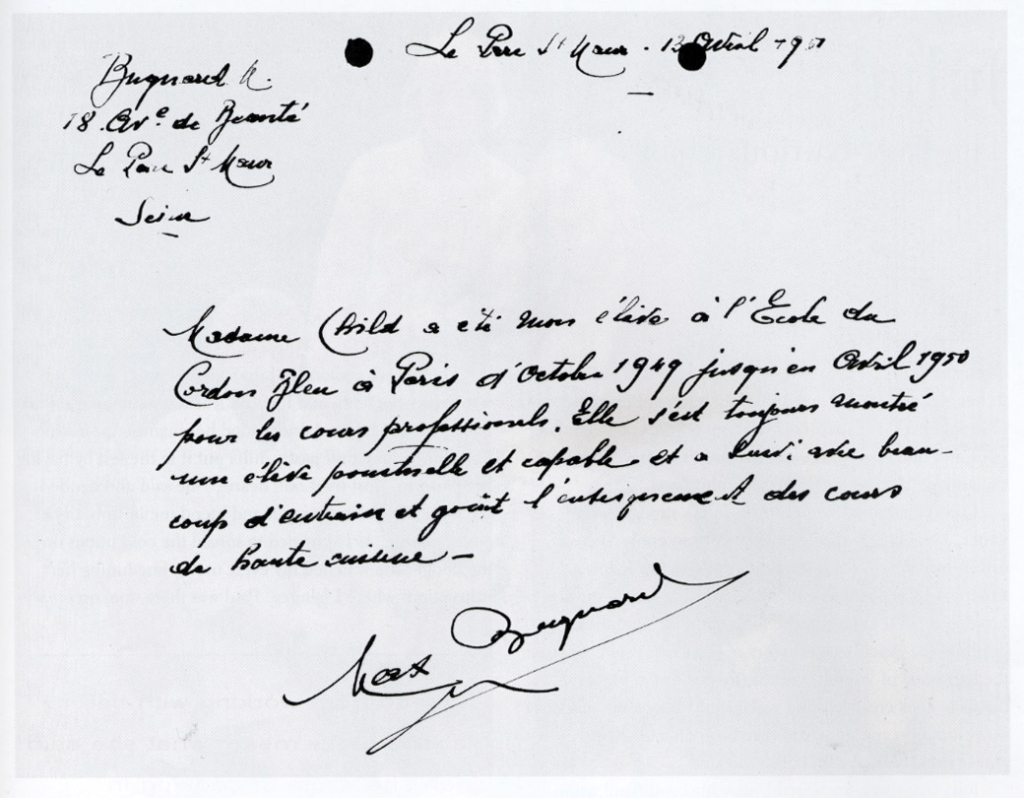

She frequently talked about her mentor at the Cordon Bleu, Chef Max Bugnard, who had once worked with Escoffier and had run his own restaurant in Brussels. Squat, with a big moustache and round, thick-rimmed glasses, ”he looked a bit like a walrus,” Julia chuckled, “and he was a great teacher.” It was Bugnard who instructed Julia how to season a frying pan, shop for wild game, and flip an omelet “with the courage of your conviction.” As a cooking teacher, he was a role model who tutored her on the importance of “theme and variation” in recipes, a lesson she would repeat her entire career. Bugnard recognized that underneath her warm humor, “Mrs. Scheeld” was for more serious and rigorous in her cooking than her classmates, eleven US servicemen studying under the GI Bill. He quietly took Julia under his wing and introduced her around the old Les Halles marketplace to his favorite wine and meat puryeyors; later, he helped Julia get her diploma from the disagreeable owner of Le Cordon Bleu; and he was a frequent guest chef al Julia’s own cooking school, l’Ecole des Trois Gourmandes. She remained grateful to “my dear old chef.” who “always taught you something new.”

Recomposing these stories from a half century ago was a collaborative effort, and our book grew in fits and starts. If Julia was well rested and feeling good, then she could pick up almost any conversational thread and explain who the players were and what the context was. Her puckish humor always shone through, as when she described how she learned lo converse like a Frenchwoman: “If you wanted to be heard at a dinner party, you had to talk very loud, and very fast, and to have a very firm opinion about whatever it was, or else you’d be ignored. It drove Paul crazy, but I thought it was great fun.”

Some of our best conversations took place when we were “off duty,” driving to a nearby rose farm, or visiting a cat show or eating lamb chops at a restaurant down the street. One day, as I was rolling her wheelchair through Santa Barbara’s famous farmers’ market, where she seemed to know every olive, strawberry, and avocado vendor, she told me that one of the most important lessons she had learned in France was how to shop: “Shopping in Paris was life changing. It taught me all about food, of course, but also about les human relations. If I didn’t take the time to talk to the sellers and learn about what they were selling, then I wouldn’t go home with the freshest head of lettuce or best bit of steak in my basket. … If you did ask about their wares and themselves, the French would just open right up. They were so generous.”

Letter from Max Bugnard attesting to Julia Child’s completion of the Cordon Bleu course.

Indeed, the French embraced the openhearted, six-foot-two-inch Julia, who had a knack for charming grumpy policemen, mean waiters, and her “sour-ball” husband, a habit Paul described as “la Juliafication des gens.” Her enthusiasm was her secret weapon, and she used it to talk her way into the back rooms of brasseries, fromageries, boucheries, patisseries, and vineyards all over France, where she’d inevitably convince the chef or Madame La Patronne to spill the secrets of their special duck dish or loaf of bread. When I asked how she managed to obtain this proprietary information, she explained, “Well, I was really interested in what they had to say, and no one else was. My friends, both French and American, all employed femmes de menage to help with housework. They thought I was insane for wanting to do the shopping, cooking, and cleaning by myself, but I just thought it was fun.”

The book we wrote, tentatively titled Bon Appetit: My Life in France with Paul , is narrated by Julia in the first person. Because her speech and writing rhythms were so different from mine-or from most people’s, for that matter-it took some work to get her voice onto the page in a natural-sounding way. Julia described herself as a “kitchen-gadget freak” who liked to “plop” things on the counter, enjoyed “crackerjack works of art,” cried “Woe!” or “Yipppee!” and thought that a good meal was “Yum!” Paul’s letters were better than hers in explaining their daily lives in Paris and Marseille, and so the voice of the book is really that of

“Pulia,” a signature they sometimes used, a combination of the two of them.

One day last August, about a week before her death, Julia was napping while I worked at her desk. Suddenly she began to stir and talk in her sleep: ‘You left me,” she said. “I miss you. Where are you? Where are you?” It seemed clear that she was talking to Paul, whose photograph stood guard on her bedside table. Julia saw Bon Appetit as a tribute to him: “I would never have had my career without Paul,” she said many times.

Listening to her stories, it was easy to imagine Paul-quiet, urbane, nattily dressed, bald with a moustache and glasses-and Julia-towering, loud, inquisitive, with a pile of curly brown hair and size-twelve sneakers-laughing over champagne and oysters portugaises at Cafe Lipp, driving along the sparkling Seine in their “Blue Flash” Buick, poking their heads into a restaurant kitchen to ask the chef just how she’d made that wonderful beurre blanc, or exploring the cobblestoned byways of Montmartre as the sun set and the lights of Paris began lo shine in the dark.